The ultimate science-backed guide to improving cycling performance with personalized nutrition

Okay cyclists, listen up. Whether you want to improve your endurance on the bike or build speed, your nutrition matters. A lot. Here’s everything you need to know about optimizing your performance on the bike through personalized nutrition.

Contents

Physiological changes that occur during a ride How many calories do cyclists need? Carbohydrates needs for cyclists Protein requirements for cyclists How much fat do cyclists need? Special diets and cycling performance What to eat before, during, and after a bike ride Hydration requirements for cyclists The best ergogenic aids and supplements for cycling performance Summary Key TakeawaysBefore we get into nutrition recommendations, it’s important to understand what’s going on internally when you’re on the bike.

Physiological changes that occur during a ride

During a ride, several physiological changes take place which impact your nutrient needs. These include fuel store depletion, changes in hydration levels, inflammation, and immune system suppression. The good news is that with careful consideration and optimal nutrition, you can mitigate these effects and improve performance.

Fuel store depletion

Glycogen is the stored carbohydrate in your muscles and liver. Once available glucose is used, your body starts converting glycogen to glucose to fuel your ride. On average, both of these stores are depleted after 60-90 minutes of high-intensity endurance training or 120 minutes of moderate-intensity (~65% VO2max)[1]. (Find out how to use your Apple Watch to calculate VO2 max here

Dehydration

Nutrition for cyclists is not just about food -- fluid is critical for performance too. Exercise rapidly increases your internal temperature and water keeps you cool via the sweat-evaporation process. The harder you work, the more water you need for this process, and staying ahead of dehydration is essential for preventing heat exhaustion and heat stroke, especially on warm training days.

But more than that, proper hydration levels keep your cardiovascular system operating efficiently, which is obviously critical for cycling performance. Water also helps lubricate your joints, stabilize your heart rate, and access fuel locked up in your cells [2]. Studies show that even a 2% dip in body mass due to fluid loss can impair endurance performance and capacity. At 5%, work capacity decreases by 30% [3].

Inflammation and immune system suppression

Ever found yourself with a cold following a race? There’s a reason for that. Sustained, high-intensity exercise compromises gut barrier function and can make you more susceptible to illness [4]. Moreover, prolonged and intense physical strain increases inflammation. Adequate nutrition before, during, and after your ride can help get your body back on track, stay healthy and recover faster.

How many calories do cyclists need?

No surprises here -- both the quality and the quantity of food are important considerations for cyclists. Macronutrients include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, and play an important role in your performance as an athlete.

If you’re riding at moderate to intense levels, anywhere from 2-6 hours/day, 5-6 days/week, your energy expenditure can hover between 600-1200 kcalories (kcal) per hour on the bike. In practice, most cyclists need 2,000-7,000 kcal/day (or more) depending on body weight and training load [4]. (Yes, that’s right. Some cyclists need 7000kcal or more!).

Energy requirements for cyclists can be anywhere between 2,000-7,000 kcal/day, depending on your body weight and training load [4].

And not surprisingly, negative energy balance, or constant low energy availability, can not only compromise your performance but also your physical health.

A simple way to ensure that your calorie intake matches your energy expenditure is to track your dietary intake in a food tracking program such as My Fitness Pal

No time to track your intake? Alternatively, you can pay attention to internal hunger and satiety cues and use those as a guide. Our bodies are pretty competent at letting us know when to eat and when to stop.

Now, let’s dive deeper into individual macronutrients.

Carbohydrates needs for cyclists

Carbohydrates are the preferred fuel of the brain and working muscles and an important consideration before, during, and after your ride, particularly when your ride is more than 90 minutes. Below are the reference ranges for carbohydrate intake based on activity level:

Normal activity level 45%-55% CHO [3–8 g/kg/day]

Endurance athlete >2hr training / day: >60% CHO [5–8 g/kg/day]

The longer and harder you cycle, the more carbohydrates you need.

Carbohydrates are classified as either high-glycemic (rapidly digested and absorbed) or low glycemic (slowly digested and absorbed). High fiber, low glycemic carbohydrates offer a myriad of health benefits and generally provide more nutrients than refined, high glycemic carbohydrate choices. That said, high glycemic carbohydrates such as sports drinks, juice, and gels can be useful immediately before, during, and after exercise to minimize GI distress, speed up recovery and provide energy. Yes, you read that correctly. Refined carbohydrates have a place for cyclists, and that place is before, during, and after a ride.

Carbohydrate-rich foods include:

Whole Grains: rolled oats, rice, farro, barley, quinoa, sprouted grain bread, granola

Starchy vegetables: sweet potato, potato, squash

Fruit

Dried Fruit

Nutrition bar with >25g carb and <5g fiber per serving

Refined grains (higher glycemic): white bread, bagels, pasta, cereals, juice

Protein requirements for cyclists

Now, onto another popular topic among athletes: protein. Protein is composed of various amino acids and plays an integral role in cell regulation, nerve function, and muscle synthesis [5]. It also helps you feel full and can even assist some people with weight loss [6]. For cyclists, adequate high-quality protein, at the right time is essential for performance, recovery, and training progression.

Some amino acids are non-essential, meaning your body can synthesize them from other compounds, however, other amino acids are essential and need to be obtained from food. High-quality meats, eggs, fish, soy, beans and legumes, and protein powder are all sources of protein.

The recommended intake for protein ranges from 0.8-1.2 g/kg/day but athletes may need up to 2.2g/kg/day [7]. This means for a 150lb athlete, daily protein intake should fall somewhere between 70-150g. Cyclists looking to increase lean muscle mass, and lose body fat may especially benefit from hitting their protein target.

To break it down: If you are eating 55%-60% of your total calorie intake from carbohydrates, aim for 15-20% of your calories from protein [8].

How much fat do cyclists need?

Fats play an important role in insulating organs, cushioning joints, and providing energy, particularly during lower-intensity exercise. While there is no evidence to suggest that athletes need to consume a greater proportion of their total calories from fat, choosing high-quality fats can support hormonal health and inflammation, both of which are a concern during prolonged high-intensity exercise [8].

The recommended daily intake for fat is 0.5-1.5 g/kg/day. If you are getting 55-60% of your calories from carbohydrates and 15-20% from protein that leaves you with 20-30% of your calories coming from fat [4].

Mono and polyunsaturated fats are the ‘healthy’ fats that can be incorporated into each meal. These fats come from food sources including nuts and seeds, olives and olive oil, avocado, and fatty fish.

Omega-3 fatty acids

Speaking of fatty fish…omega-3 fatty acids are a group of fats that fight inflammation and may help promote muscle recovery post-exercise. Furthermore, research suggests that omega-3 fats are beneficial for heart health, liver function, hormones, and more [9, 10, 11].

There are two dietary sources of Omega-3s: EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DPA (docosahexaenoic acid). Food sources of EPA and DHA include fatty fish such as salmon and tuna. ALA (alpha-linolenic acid), the plant-based source of Omega-3s, comes from flaxseed, nuts, and vegetable oils.

Most health benefits of omega-3s come from EPA and DHA food sources rather than ALA. ALA can be converted to EPA, however, the conversion rate is low (~5%). If you’re not eating fatty fish at least 2 times a week, a supplemental dose of omega - 3s can be helpful for recovery and overall health [12].

Special diets and cycling performance

Perhaps you’re a keto-enthusiast? Or a die-hard vegan? Specific diets such as vegan or vegetarian, paleo and keto, have become more popular among endurance athletes over the last few years. Each has perks and pitfalls.

Vegetarianism/ veganism

If you’re a cyclist following a vegan or vegetarian diet, be mindful of protein sources since plant-based foods tend to offer less protein and this is important for building muscle. Micronutrients such as B vitamins, iron, and zinc, also require extra attention, since these are less available or absent in plant foods and can dramatically impact cycling performance, energy levels, and overall health [13].

Keto

In case you haven’t come across it before, a ketogenic diet is a high-fat, very low carbohydrate diet, where carbs are typically restricted to less than 50g per day. Relying on fat (in the form of ketones) as your primary fuel source has limited and mixed efficacy for endurance athletes such as cyclists [4].

Relying on fat (in the form of ketones) as your primary fuel source has limited and mixed efficacy for endurance athletes such as cyclists [4].

Paleo

Composed of predominantly lean meats, fish, fruits and vegetables, nuts, and seeds, the paleo diet omits processed sugars and starches, and grains. Eating paleo may be beneficial for endurance athletes, however, many of these reports are anecdotal and more research is needed to validate these findings. Some athletes feel better eating paleo because it relies more heavily on lean protein and healthy fats and restricts pro-inflammatory processed foods and refined sugars. However, getting adequate carbs can be tricky, and careful planning is required on high training load days to support energy requirements and recovery.

Whether you’re a keto-enthusiast or devout vegan, most of the time your goal should be to choose minimally-processed whole foods and limit refined grains, added sugars, and saturated fats. Getting enough calories can be challenging when your training load is high and nutrient-dense energy bars and protein powders can help fill gaps. There’s no “one size fits all” diet for cyclists and you have to do a little experimentation to learn what works best for you.

What to eat before, during, and after a bike ride

When you eat can sometimes be as important as what you eat for cyclists. Fueling up adequately (and smartly) pre-ride can be the difference between crushing your workout and bonking midway through. So, let’s get into the nitty-gritty.

2-4 hours before your ride

Aim to eat your last full meal 2-4 hours before your ride. Your goal should be a balanced meal that includes carbohydrates, protein, and fat. However, carbohydrates should be the focus and some cyclists need 50-100 grams of carbohydrates in their pre-workout meal. Eating carbohydrate pre-workout helps top off glycogen stores and provides readily-available fuel for working muscles when you get on the bike [14, 15].

Below are a few ideas for pre-workout meals:

Oatmeal topped with banana, berries, and nut butter

Sandwich on whole-grain bread with turkey, avocado, lettuce, and tomato

Rice bowl with tofu, avocado, and baby greens

15-30 minutes before your ride

15-30 minutes before your workout, easily digestible carbohydrates low in fiber, protein, and fat, are generally the best choice. Options include:

Banana

8oz sports drink

Energy gel

Should you eat before your early-morning ride?

Glycogen stores diminish overnight and getting in a little carbohydrate-rich fuel prior to jumping on the bike can be beneficial, especially if you have a long or intense session planned.

If you decide to go out fasted and are planning on cycling for longer than 90 minutes, aim to consume a small amount of sports drink or gel every 15-30 minutes to prevent bonking. If your workout is 90 minutes or less, you might be able to get away with refueling post-workout, however, take a backup snack on your ride just in case [4].

How to refuel after your bike ride

The optimal time to refuel is 15-60 minutes post-workout [16]. Basically, the sooner you can start replenishing fuel and fluid, the better!

After a ride, the most important nutrients to consume are carbohydrates, protein, and fluid. Water or an electrolyte beverage is essential to replete fluids, protein initiates muscle protein synthesis (MPS), and carbohydrates replenish lost muscle and liver glycogen stores.

The optimal time to refuel is 15-60 minutes post-workout [16].

Eating a combination of carbohydrates and protein post-ride is more effective than either nutrient alone. In fact, skipping carbs and consuming only protein after endurance exercise reduces the rate of glycogen storage and, in turn, delays recovery [17].

Within 60 minutes post-workout aim for:

Carbohydrate: 45-90g, depending on your body weight and the intensity of your ride. The longer and harder you work the more you need. Rapidly absorbed sources of carbohydrates like sports drinks, fruit, juices, smoothies, white bread, etc are ideal.

Protein: 25-40g protein (0.4 to 0.5 g/kg or 0.9 to 1.1 g/lb) to optimize muscle synthesis and promote recovery [18]. Protein sources rich in leucine (a branched-chain amino acid) such as dairy products, whey protein, eggs, and beef, seem to be especially effective for muscle protein synthesis.

Hydration requirements for cyclists

Slurp up, cyclists! The importance of hydration cannot be overstated. Just about every biological process depends on a sufficient supply of water, so keeping yourself hydrated before, during, and after cycling is key to performing at your best. As little as a 2% drop in body weight due to fluid loss can impair performance and impact cardiac output [4].

Hydration during the day

Aim to consume ½ oz fluid per pound of bodyweight. For example, if you weigh 190lb (86kg), you should drink 95oz (3L) of water a day, plus additional fluid before, during, and after a workout [2]. Water, sparkling water, and tea are all great hydration options.

Hydration before a ride

Adequate hydration pre-workout can help prevent dehydration and prepare your body for your upcoming ride. Aim for urine that is light to pale yellow in color before you get on the bike. Below are some rough guidelines for pre-ride fluid intake, although hydration needs vary from person-to-person (we see you, heavy sweaters). Water is generally the best option, however, some people may benefit from adding sports drinks into their pre-ride routine, especially if you’re planning a long ride and/or you’re a salty sweater.

2-3 hours before your ride: 16oz (2 cups);

15-30 minutes before your ride: 8oz (1 cup)

Fluid intake during a ride

The longer and harder your ride, the more fluid you need to replace while you’re on the bike. A good rule of thumb is to aim for 4oz (½ cup) of fluid, as either water or a sports drink, every 20 minutes.

During your ride: 4oz (½ cup) every 20 minutes [19].

Hydration needs after a ride

Post-ride it’s all about replenishing the fluids and electrolytes you lost on the bike. One easy way to measure fluid losses is to weigh yourself before and after a workout. You need roughly 16oz (2 cups) of fluid for every 1lb (0.5kg) lost. Don’t have a scale nearby? You can always use urine color as an approximation of hydration status. Urine lemonade or lighter generally means that you’re hydrated.

Do cyclists need electrolytes?

Sports drinks and electrolytes can be a confusing topic for cyclists to navigate. So, let’s start with the basics.

Electrolytes are electrically charged minerals including sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and chloride. They are critical for muscle and nerve function and help regulate fluid balance. Both water and electrolytes are lost through sweat and adding a sports drink or electrolyte supplement before, during, and after your workout can help you stay stronger for longer, as well as reduce your risk of heat illness and cramping, under certain conditions [20].

Electrolyte and fluid losses vary from person-to-person and are influenced by factors such as heat. If you notice white crystals on your jersey and forehead after a relatively short ride, you’re probably a “salty sweater” and may need to start replenishing your electrolytes earlier than other cyclists. That said, not everyone needs an electrolyte supplement after every ride. If you’re going out for a short, easy ride in cooler conditions, water may suffice for fluid repletion.

In general:

Aim to consume 4oz of sports drinks (½ cup) every 15-20 minutes if you’re a salty sweater, plan on being on the bike for more than 45 minutes, or are riding in warm conditions.

Carbohydrate-containing sports drinks are also a convenient way to top up your glucose supply, as well as replete fluid and electrolytes.

A good rule of thumb is to incorporate about 14 g of carbohydrates, 28mgs of potassium, and 100 mg of sodium per 8oz fluid (1 cup).

If you’re a salty sweater, plan on the bike for longer than 45 minutes, or are cycling in hot conditions, aim to consume 4oz of sports drinks (½ cup) every 15-20 minutes.

The best ergogenic aids and supplements for cycling performance

Brace yourself. This is a complicated topic, but it’s worth understanding, especially if you’re looking to take your cycling performance to new heights. While there are many supplements out there for cyclists, not all of them are safe and effective.

What are ergogenic aids?

Ergogenic aids are substances that enhance physical performance, improve energy, and/or promote recovery. We’ve already touched on protein powder, omega-3s, and electrolytes -- here’s the science-backed scoop on other supplements commonly used in cycling:

Tart cherry juice

Tart cherry juice is loaded with antioxidants and polyphenolic compounds, and increasingly popular among endurance athletes. Some evidence suggests that taking tart cherry juice prior to endurance activities like cycling may improve performance and reduce muscle soreness, although research is mixed [22].

Tart cherry juice can be found in various forms including juice, capsule, and concentrate, and dosage recommendations vary depending on the preparation. If you want to experiment with tart cherry juice for cycling performance, look for a product without additives and take at least 1.5 hours before you jump on the bike.

Turmeric

Turmeric has been used for centuries as a traditional remedy for everything from digestive issues to skin health, and now a growing body of evidence suggests that it may have performance benefits too. Although turmeric contains many compounds, curcumin -- the substance that gives turmeric its bright yellow hue -- seems to be responsible for its anti-inflammatory benefits.

Small studies indicate that 150-1500mg turmeric/day may improve post-exercise recovery and reduce muscle soreness, however, the evidence to-date is mixed [23]. Turmeric may also be helpful for reducing knee pain in people with osteoarthritis, a common complaint among older athletes [24]. Combining turmeric with black pepper has been shown to improve absorption of curcumin by up to 2000%(!) and increase its effectiveness [23].

Caffeine

Caffeine is one of the most widely used ergogenic aids in sport. Found in everything from coffee to sports gels, caffeine stimulates the central nervous system and is believed to boost energy and alertness by blocking adenosine receptors. Studies show that consuming caffeine prior to exercise may result in improved performance, speed, power, and endurance capacity [26].

Anyone who’s overdone it on coffee knows that you can have too much of a good thing. Aim for 3-9 mg caffeine/kg, 30 - 90 minutes before you get on the bike for a total of no more than 400-500mg caffeine per day (roughly 4-5 cups of coffee) to enjoy performance-enhancing benefits without unpleasant side effects [4, 27]. Studies show limiting caffeine intake to 50 mg/day or cutting out caffeine altogether for 2-7 days before a race might maximize its effect [4, 27].

Aim for 3-9 mg caffeine/kg, 30 - 90 minutes before exercise for a total of no more than 400-500mg caffeine per day (roughly 4-5 cups of coffee) to enjoy performance benefits without unpleasant side effects [4, 27].

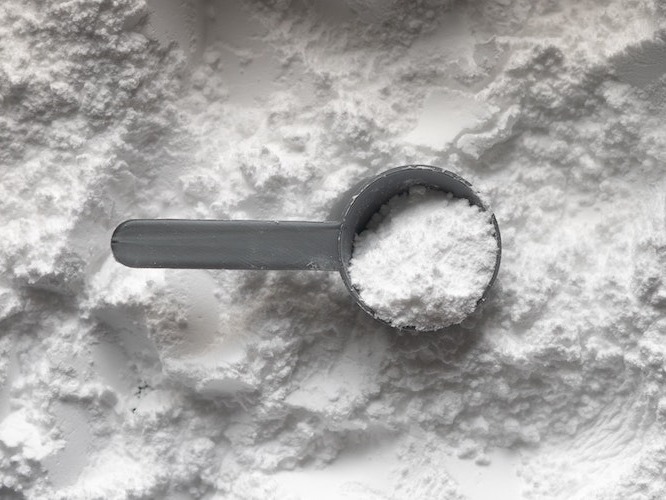

Creatine

Creatine is a dietary amino acid found in many foods. One of the most widely studied supplements for athletic performance, our body relies on creatine for power activities and recovery. Although typically thought of as a supplement for power athletes, creatine may benefit endurance athletes like cyclists too.

Research shows that creatine supplementation may improve muscular strength and body composition, enhance recovery, and boost speed, although the precise impact on cycling performance is still being explored [28].

Research shows that creatine supplementation may improve muscular strength and body composition, enhance recovery, and boost speed, although the precise impact on cycling performance is still being explored [28].

Curious to try creatine? Look for creatine monohydrate and begin with a loading dose of 20g per day for 5 days, followed by 3 - 5g per day thereafter [27, 28]. Splitting the dose over multiple meals can be helpful for preventing adverse side effects such as nausea and diarrhea.

It’s also worth noting that creatine can cause modest weight gain in some athletes and adequate hydration is recommended to avoid stomach cramps.

Sodium bicarbonate

If you’re thinking that this one sounds familiar - you’re right. Sodium bicarbonate is commonly known as baking soda and has been studied as a performance-enhancing aid because of its ability to buffer lactic acid build-up during exercise [29]. High-intensity exercise causes lactic acid production, and lactic acid build-up is a major contributing factor to muscle fatigue. (Hello, post-workout lead legs).

Small studies suggest that sodium bicarbonate dosed at 0.3g per kg, can help reduce fatigue and improve performance during high-intensity activities less than 4 minutes, however, it seems to be less impactful for endurance activities like cycling [30].

Beta-alanine

Beta-alanine is an amino acid and precursor to carnosine -- a compound found in muscles that buffers lactic acid production. Evidence to-date shows that beta-alanine may help improve performance and reduce neuromuscular fatigue, although the impact on endurance activities like cycling is not well-understood [31]. The optimal dosage of beta-alanine appears to be 4-6g per day, split over 2 doses, for 2-4 weeks [32, 33].

Magnesium

Magnesium plays a critical role in protein synthesis, bone health, and muscle function, and is largely under-consumed. Stress and sweat deplete magnesium stores and cyclists may benefit from additional magnesium intake. Moreover, some studies suggest that magnesium can be helpful for sleep and relaxation - two critical components of exercise recovery [21].

Magnesium-rich foods include spinach, peanuts, almonds, cashews, legumes, bananas, and whole grains. Supplemental magnesium with approximately 300mg of magnesium glycinate/citrate, is also an option prior to bed.

Summary

A precisely-calibrated nutrition routine can help you stay ahead of the competition, recover faster and minimize wear and tear. It can be the difference between a terrible ride and a great one and can help you realize your peak potential. No two cyclists are the same and while recommendations are helpful, it's important to experiment in training to find what works for you and your unique biochemistry.

Disclaimer: The text, images, videos, and other media on this page are provided for informational purposes only and are not intended to treat, diagnose or replace personalized medical care.

Key Takeaways

Carbohydrates are the preferred fuel of the brain and working muscles and an important consideration before, during, and after your ride.

For cyclists, adequate high-quality protein, at the right time is essential for performance, recovery, and training progression.

Fueling up adequately and smartly pre-ride can be the difference between crushing your workout and bonking midway through.

Just about every biological process depends on a sufficient supply of water, so keeping yourself hydrated before, during, and after cycling is key to performing at your best.

Omega-3s, protein powder, electrolytes, tart cherry juice, caffeine, and creatine are a few ergogenic aids examples that can help take your cycling performance to new heights.

References

Murray, B., & Rosenbloom, C. (2018). Fundamentals of glycogen metabolism for coaches and athletes. Nutrition reviews, 76(4), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuy001

Popkin, B. M., D'Anci, K. E., & Rosenberg, I. H. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition reviews, 68(8), 439–458.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x

JEUKENDRUP, A., & GLEESON, M. (n.d.). Dehydration and its effects on performance. Retrieved February 05, 2021, from https://us.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/dehydration-and-its-effects-on-performance

Kerksick, C.M., Wilborn, C.D., Roberts, M.D. et al. ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 15, 38 (2018).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-018-0242-y

Daniel R Moore, One size doesn't fit all: postexercise protein requirements for the endurance athlete, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 112, Issue 2, August 2020, Pages 249–250, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa144

Leidy, H. J., Clifton, P. M., Astrup, A., Wycherley, T. P., Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S., Luscombe-Marsh, N. D., Woods, S. C., & Mattes, R. D. (2015). The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 101(6), 1320S–1329S.

https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.084038

Phillips, S. M., & Van Loon, L. J. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of sports sciences, 29 Suppl 1, S29–S38.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2011.619204

Williams C. (1995). Macronutrients and performance. Journal of sports sciences, 13 Spec No, S1–S10.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419508732271

Office of dietary supplements - omega-3 fatty acids. (2020, October 1). Retrieved February 03, 2021, from

https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-Consumer/

VanDusseldorp, T. A., Escobar, K. A., Johnson, K. E., Stratton, M. T., Moriarty, T., Kerksick, C. M., Mangine, G. T., Holmes, A. J., Lee, M., Endito, M. R., & Mermier, C. M. (2020). Impact of Varying Dosages of Fish Oil on Recovery and Soreness Following Eccentric Exercise. Nutrients, 12(8), 2246.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082246

Marshall, R. N., Smeuninx, B., Morgan, P. T., & Breen, L. (2020). Nutritional Strategies to Offset Disuse-Induced Skeletal Muscle Atrophy and Anabolic Resistance in Older Adults: From Whole-Foods to Isolated Ingredients. Nutrients, 12(5), 1533.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051533

Publishing, H. (n.d.). Omega-3-rich foods: Good for your heart. Retrieved February 03, 2021, from

https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/omega-3-rich-foods-good-for-your-heart

Woolf, K., & Manore, M. M. (2006). B-vitamins and exercise: does exercise alter requirements?. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 16(5), 453–484.

https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.16.5.453

Mata, F., Valenzuela, P. L., Gimenez, J., Tur, C., Ferreria, D., Domínguez, R., Sanchez-Oliver, A. J., & Martínez Sanz, J. M. (2019). Carbohydrate Availability and Physical Performance: Physiological Overview and Practical Recommendations. Nutrients, 11(5), 1084.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11051084

Pendergast, D. R., Horvath, P. J., Leddy, J. J., & Venkatraman, J. T. (1996). The role of dietary fat on performance, metabolism, and health. The American journal of sports medicine, 24(6 Suppl), S53–S58.

Lemon, P. W., Berardi, J. M., & Noreen, E. E. (2002). The role of protein and amino acid supplements in the athlete's diet: does type or timing of ingestion matter?. Current sports medicine reports, 1(4), 214–221.

https://doi.org/10.1249/00149619-200208000-00005

Ivy, J. L., Katz, A. L., Cutler, C. L., Sherman, W. M., & Coyle, E. F. (1988). Muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise: effect of time of carbohydrate ingestion. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 64(4), 1480–1485.

https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1988.64.4.1480

Schoenfeld, B. J., Aragon, A., Wilborn, C., Urbina, S. L., Hayward, S. E., & Krieger, J. (2017). Pre- versus post-exercise protein intake has similar effects on muscular adaptations. PeerJ, 5, e2825.

https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2825

Backes, T. P., & Fitzgerald, K. (2016). Fluid consumption, exercise, and cognitive performance. Biology of sport, 33(3), 291–296.

https://doi.org/10.5604/20831862.1208485

Maughan R. J. (1991). Fluid and electrolyte loss and replacement in exercise. Journal of sports sciences, 9 Spec No, 117–142.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419108729870

Lukaski,Henry C. Magnesium, zinc, and chromium nutriture and physical activity, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 72, Issue 2, August 2000, Pages 585S–593S, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.2.585S

Gao, R., & Chilibeck, P. D. (2020). Effect of Tart Cherry Concentrate on Endurance Exercise Performance: A Meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 39(7), 657–664.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2020.1713246

Yoon, W. Y., Lee, K., & Kim, J. (2020). Curcumin supplementation and delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS): effects, mechanisms, and practical considerations. Physical activity and nutrition, 24(3), 39–43.

https://doi.org/10.20463/pan.2020.0020

Paultre, K., Cade, W., Hernandez, D., Reynolds, J., Greif, D., & Best, T. M. (2021). Therapeutic effects of turmeric or curcumin extract on pain and function for individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine, 7(1), e000935. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000935

Office of dietary supplements - dietary supplements for exercise and athletic performance. (2019, October 17). Retrieved February 04, 2021, from

https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/ExerciseAndAthleticPerformance-HealthProfessional

Wiles, J. D., Coleman, D., Tegerdine, M., & Swaine, I. L. (2006). The effects of caffeine ingestion on performance time, speed and power during a laboratory-based 1 km cycling time-trial. Journal of sports sciences, 24(11), 1165–1171.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410500457687

Shearer,Jane., Graham, Terry E., Performance effects and metabolic consequences of caffeine and caffeinated energy drink consumption on glucose disposal, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 72, Issue suppl_1, 1 October 2014, 121–136, https://doi.org/10.1111/nure.12124

Rawson, E. S., Miles, M. P., & Larson-Meyer, D. (2018). Dietary Supplements for Health, Adaptation, and Recovery in Athletes, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(2), 188-199. Retrieved Feb 4, 2021, from

https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/28/2/article-p188.xml

Hadzic, M., Eckstein, M. L., & Schugardt, M. (2019). The Impact of Sodium Bicarbonate on Performance in Response to Exercise Duration in Athletes: A Systematic Review. Journal of sports science & medicine, 18(2), 271–281.

McNaughton, Lars R.; Siegler, Jason; Midgley, Adrian Ergogenic Effects of Sodium Bicarbonate, Current Sports Medicine Reports: July-August 2008 - Volume 7 - Issue 4 - p 230-236 https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0b013e31817ef530

Trexler, E. T., Smith-Ryan, A. E., Stout, J. R., Hoffman, J. R., Wilborn, C. D., Sale, C., Kreider, R. B., Jäger, R., Earnest, C. P., Bannock, L., Campbell, B., Kalman, D., Ziegenfuss, T. N., & Antonio, J. (2015). International society of sports nutrition position stand: Beta-Alanine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 12, 30.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-015-0090-y

Hobson, R. M., Saunders, B., Ball, G., Harris, R. C., & Sale, C. (2012). Effects of β-alanine supplementation on exercise performance: a meta-analysis. Amino acids, 43(1), 25–37.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-011-1200-z

Peeling, P., Binnie, M. J., Goods, P..R., Sim, M., & Burke, L. M. (2018). Evidence-Based Supplements for the Enhancement of Athletic Performance, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(2), 178-187. Retrieved Feb 5, 2021, from

https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/ijsnem/28/2/article-p178.xml