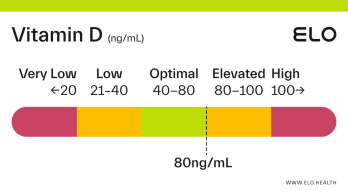

Vitamin D: 80 ng/mL

What does a vitamin D level of 80 mean? Are there any symptoms associated with this vitamin D level?

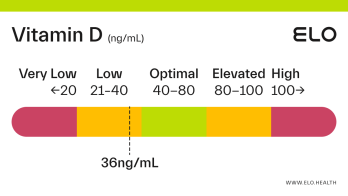

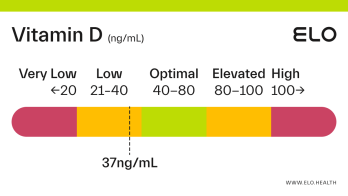

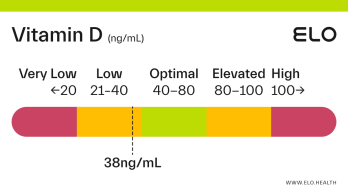

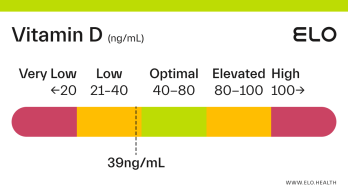

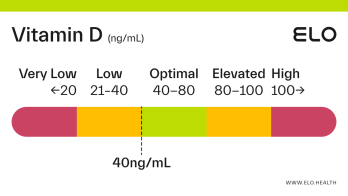

A vitamin D level of 80 ng/mL is considered elevated. Elevated vitamin D can occur from over-supplementation of vitamin D, excessive exposure to sunlight or artificial UV light (tanning beds), and overconsumption of high vitamin D foods such as cod liver oil [1].

A level of 80 ng/mL is the lowest reported level associated with toxicity in people with normal kidney function [2]. A level at or above 80 ng/mL may put you at greater risk for developing vitamin D toxicity over time, though adverse effects are typically only observed at levels >125 ng/mL [1].

Vitamin D toxicity is usually caused by large doses of vitamin D supplements — not by diet or natural sun exposure [1]. Symptoms of toxicity include fatigue, weight loss, loss of appetite, excessive thirst and urination, constipation, dehydration, nausea/vomiting, muscle weakness, ringing in the ear, confusion, and heart arrhythmias.

Factors that could contribute to a vitamin D level of 80

Over-supplementation of vitamin D

Frequent, prolonged sun exposure (i.e. multiple hours per day most days)

Frequent tanning bed use

Overconsumption of high vitamin D foods such as cod liver oil

While excessive sun exposure can result in elevated vitamin D levels, it is not thought to cause toxicity because thermal activation of pre-vitamin D3 in the skin gives rise to various non-vitamin D forms that limit the formation of vitamin D3 [1]. Some vitamin D3 is also converted to inactive forms. Unlike the sun, frequent use of tanning beds, which provide artificial UV radiation, can lead to toxicity (levels >125 ng/mL).

What to do if your vitamin D level is 80?

To reduce vitamin D levels:

If supplementing, reduce the amount and/or frequency of vitamin D you are taking, or stop supplementing altogether until levels return to the optimal range.

Stop buying and consuming foods fortified with vitamin D as these will contribute to your overall supplementation levels.

Stop use of tanning beds

Avoid excessive sun exposure by spending less time in the sun and wearing sunscreen and protective clothing.

References

National Institutes of Health. (2021, March 26). Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D. National Institutes of Health – Office of Dietary Supplements.

https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

Kennel, K. A., Drake, M. T., & Hurley, D. L. (2010). Vitamin D deficiency in adults: when to test and how to treat. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 85(8), 752–758.

https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0138

Alshahrani, F., & Aljohani, N. (2013). Vitamin D: deficiency, sufficiency, and toxicity. Nutrients, 5(9), 3605–3616.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5093605

Holick M. F. (2009). Vitamin D status: measurement, interpretation, and clinical application. Annals of epidemiology, 19(2), 73–78.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.001

Demir, M., Demir, F., & Aygun, H. (2021). Vitamin D deficiency is associated with COVID-19 positivity and severity of the disease. Journal of medical virology, 93(5), 2992–2999.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26832

Kayaniyil, S., Vieth, R., Retnakaran, R., Knight, J. A., Qi, Y., Gerstein, H. C., Perkins, B. A., Harris, S. B., Zinman, B., & Hanley, A. J. (2010). Association of vitamin D with insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in subjects at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care, 33(6), 1379–1381.

https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-2321

Examine.com. (2019, April). A D-fence against cancer?

https://examine.com/members/deep-dives/article/a-d-fence-against-cancer/

Yang, C. Y., Leung, P. S., Adamopoulos, I. E., & Gershwin, M. E. (2013). The implication of vitamin D and autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 45(2), 217–226.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-013-8361-3